Asia's Emerging R&D Hotspots

The economic lure of Asia attracts a wave of new R&D

investments and opportunities.

New R&D clusters are emerging in Asia, and the

way they attract talent, nurture academic and commercial

ventures, and operate could be models for other research

centers around the world.

Click

here to enlage

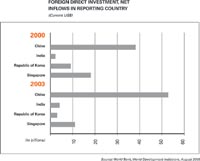

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, August 2005 Click

here to enlage

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, August 2005 |

Whether it’s a quickly growing suburb in China,

or an established urban area in South Korea, there

are a few constants among these new emerging “hotspots” in

Asia; local governments, recognizing the importance

of infrastructure and support services to attract companies,

are making an investment; more money is being directed

toward universities for research, and more emphasis

placed on academic-commercial collaboration; and finally,

locally trained technical talent, who once fled for

better opportunities in other countries, are now digging

in, or returning from abroad, to start new businesses

or to run local subsidiaries of multinationals.

R&D explosion

“

There’s everything in Asia, from the traditional

R&D centers to the newer to the newest,” observes

Wei Li, associate professor of business administration,

Darden School of Business at Univ. of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Both developed and developing countries alike are

discovering strengths in the R&D market and playing

to them. South Korea is focused on electronics; Singapore

has committed considerable financial resources to

turn itself into a biotech center. China and India

are the newest and fastest growing R&D players,

says Li. In Thailand, Bangkok has successfully wooed

investment by large multinationals. The Philippines,

by touting its relatively strong infrastructure and

its tech-savvy, English-speaking population, has

a growing concentration of R&D sites.

Four of the most interesting emerging clusters in

Asia are in Beijing, Shanghai, Bangalore, and Seoul.

Each of these cities has attributes that appeal to

major multinational investors, says John Boyd, president

of The Boyd Co., Princeton, N.J., a location consulting

firm whose client portfolio includes The World Bank,

PepsiCo, and Philips. These attributes include: a

highly educated workforce, a major university, a

positive business climate, an attractive lifestyle

environment, and excellent international airline

service.

But even with these obvious advantages, Beijing,

Shanghai, Bangalore, and Seoul also present challenges

to multinational investors. In China and India, laws

and regulations to protect intellectual property

(IP) are weak. Environmental regulations, too, are

fledgling or poorly enforced, and for the highly

sought global talent pool, clean air and clean water

is an important factor in where they choose to live

and work. Poor infrastructure translates into traffic

jams and trouble getting to work. Power shortages

are a regular concern.

If addressed early in the planning phases of a new

R&D project, however, each of these challenges

can be managed.

Beijing—

To see the future of R&D in China, look at Zhongguancun.

This high-tech hub in Beijing hosts showrooms, offices

and innovation centers trumpeting the brands and

new ideas of some the world’s leading technology

companies, including Intel, Apple, Microsoft, and

others. There are also storefronts with young, smart-looking

employees assembling electronics. Some envision the

day when these small assembly shops could grow—in

part by savvy investments in research and development—into

world leaders.

Zhongguancun businesses certainly have access to

talent. The tech hub is bordered by Tsinghua Univ.

and Beijing Univ., which spawned some of the early

tech businesses that have found success outside of

China. Lenovo, which recently acquired IBM’s

$1.25 billion personal computer division, was founded

at The Chinese Academy of Sciences, which calls Zhongguancun

home. Nearby are three dozen smaller universities

giving employers access to cheap, hungry technical

talent.

Hillier’s

proposed design for a research and development campus for LG

Electronics, Seoul, South Korea. Image: Hillier Architecture

Hillier’s

proposed design for a research and development campus for LG

Electronics, Seoul, South Korea. Image: Hillier Architecture |

What’s most intriguing about Zhongguancun

is the energy and ambition of the local entrepreneurs.

They boast a kind of Silicon Valley fervor, in part

driven by ready access to news media highlighting

the successes of such companies as Google, Ebay,

and others. These business owners have some access

to foreign venture capital as well as investment

money and other support from the central government.

Seeking to grow high-tech businesses, the government

offers small- and medium-sized enterprises in Zhongguancun

access to business incubator space with cheap rents

and technical assistance.

The government is also using incentives to encourage

local university professors and returning students

to commercialize their research. “They see

themselves as the creators of the world’s future

Intels, Apples, and Microsofts and some of them probably

will be,” wrote Edward Tse, Managing Director-Greater

China, Booz Allen Hamilton, Inc., in “China’s

Five Surprises,” in Strategy + Business magazine.

Shanghai—

China’s largest city, bustling Shanghai has

ambitions to be Asia’s financial, industrial,

and commercial powerhouse. It is making great progress.

Fifteen years ago, the Pudong district was farmland.

Today, it boasts a Chicago-style skyline and attracts

a significant portion of all foreign direct investment

going into China.

Much of the investment now going into Pudong is focused

on R&D and it is being done by multinational

corporations. Honeywell, DuPont, Roche, and Rohm

and Haas are a few of the corporations that have

recently announced or inaugurated R&D centers

in Pudong. Not only will these beachheads provide

the multinational corporations access to relatively

low-cost technical talent—between 1996 and

2001, universities in China almost doubled the number

of science and engineering PhDs they graduated—it

will also give them a platform in the world’s

growing market.

But in Shanghai, as well as Beijing, certain ground

rules apply to those multinational investors interested

in building R&D centers, protecting IP, and attracting

top-notch talent—two significant initiatives

that, if not carefully planned, can work at cross

purposes.

Before construction begins, companies have to decide

what kind of research they want to do. The importance

of the research to the future of the firm will help

to determine levels of security. Companies also have

to figure out how they will collaborate with local

venture partners and how they will use their R&D

campus for the education of tech support, sales staff,

and their dealer network—all without compromising

IP. Some investors in China have done a very good

job building research centers that safeguard important

work, but their foreboding facades can make it harder

to recruit top scientists.

Seoul—

South Korea, and greater Seoul, where much of the

nation’s research and development work is

concentrated, has managed to turn itself into one

of the world’s important centers of research.

This accomplishment comes in spite of the country’s

lack of natural resources and its challenging geographical

location. South Korea is wedged between two imposing

powers. To the west is China, an economic and political

giant. To the east lies the financial powerhouse

of Japan. Pyongyang, the capital of Communist North

Korea, looms to the north. So anyone seeking lessons

on making the best of the hand they have been dealt

should look to Seoul.

R&D as a percentage of South Korea’s total

GDP is 2.9%– almost double that of China. In

2004, it boasted 79,500 international patents—again

almost double that of China (R&D magazine, September,

2005). In addition to its prominence in cloning,

its R&D work in electronics and automobile research

is strong, observes Prof. Li. Corporations account

for approximately three quarters of the nation’s

investment in R&D and South Korea’s large

corporations are, for the most part, centralized

in Seoul. Auto manufacturer Hyundai and electronics

giant LG are just a few of the firms planing to build

important research centers in the metro area.

Bangalore—

India now boasts a surging population of tech

returnees—people with advanced degrees who

fled the country for better paying jobs in Silicon

Valley, San Diego, Cambridge, and New Jersey,

and are now coming back with global experience

and contacts, money, and entrepreneurial ambitions.

These returnees, combined with investments by large

companies, are turning those urban areas in

India with leading universities, good airports, and

cultural amenities into emerging centers of

research and development.

No place better exemplifies this trend than Bangalore. It boasts

one of the largest and fastest-growing concentrations

of software and information technology- related research

activities in the world. Why? Workers there

speak English and the region graduates

some 300,000 computer engineers annually, observes

Boyd. The roster of tech giants conducting IT

research in Asia is a Who’s Who of world leaders.

Among them: Cisco, Samsung, Texas Instruments,

and Microsoft.

Cisco traces its Indian roots back to 1996 when it

launched sales and marketing operations in key cities including Bangalore.

Since then, the San Jose computer networking

giant’s interest in India has blossomed.

In October 2005, it announced plans to

invest some $1 billion in India over a

three-year-period. Those funds include a major addition

to its Bangalore R&D campus.

But the region still faces challenges. Multinationals

there grapple with weak enforcement of IP. Although

the cost of doing business is low by global

standards, it is rising due in part to the inflationary

pressures caused by the success the city has had

in luring R&D investment. Infrastructure

is strained—power outages and traffic congestion

are two manifestations—and yet growth continues.

Bangalore’s success, or failure, in solving

its problems says much about the future of modern

India, and the same goes for China and South Korea.

Steve Gifford

About the Author:

Steve Gifford, AIA, is managing principal of the

New York office of Hillier Architecture (www.hillier.com)

and is currently overseeing design of two major R&D

campuses in Asia for multinational corporations.

|